#Macedonian Court

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Whenever we think of royal families our minds tend to go to the concept of the European noble House. The House of Habsburg, the House of Windsor, the House of Stuart etc. I understand that we should look at the Ancient Greek, Macedonian & Hellenistic royal families in a different way becuase of the different family & power dynamics - could you please help us understand the difference?

Ancient Court Societies vs. Modern

Probably the biggest difference is greater organization of hierarchy. Modern royal houses have had a lot of time to evolve.

Norbert Elias’s The Court Society has become the foundational study on court systems, although it’s western-focused by intent. Nonetheless, it’s a useful introduction to how courts function with inner courts, outer courts, etc.

The biggest things to keep in mind are:

The degree of formality between court members. How “deep” and structured is the hierarchy? (Smaller courts typically have far less formality than larger ones.)

How formalized are matters of succession and marriage ties? Particularly the presence (or absence) of royal polygamy can affect that.

Court societies inevitably progress from less formal and hierarchical to more of both. We can sometimes talk about earlier court societies as chieftain-level societies versus more organized royal, or even imperial societies.

Part of the struggle first Philip, then Alexander faced was transforming a chieftain-level court system into something that would work on a (much, for Alexander) larger scale. Unsurprisingly, there was push-back against, essentially, “bureaucracy.” Nobody likes it, but the larger an area controlled, the more necessary it becomes.

Traditional Macedonian courts were fairly informal, the king being primo inter pares (first among equals). No titles were used when addressing him—he was called by his name—and the only thing expected of the speaker was to take off his hat. “King” (basileus) was used when speaking OF him. We don’t see “King ___” employed in Macedonia (at least in inscriptions) until Kassandros, who needed it to buck up his claim.

None of that means the average person could wander into the palace and start chatting up the king. He was protected by his Bodyguards (Somatophylakes), who also apparently managed access to him. Yet he was expected to sit in judgement as an appellate court, where anybody could appeal a case before him. How often this occurred no doubt depended. Philip was gone a lot, and Alexander was permanently out of Macedonia two years into his reign. Presumably his regent fulfilled the role in his absence. (As I depicted near the beginning of book 2, Rise, when Alexandros is hearing cases.) Anyway, that’s one place the “average person” could get the ear of the king. Also, it seems that he was more approachable by soldiers in battle circumstances. We’re told Alexander got right in with his men to do work during sieges. It was to encourage them, but he was standing next to them so they could see and talk to him, if they wanted to. He seems to have known many of his veterans by name.

Another factor in Macedonia was lack of formal hierarchy among nobility. They had a nobility—the Hetairoi (King’s Companions)—but theoretically all Hetairoi were equal in status. In practice, they absolutely weren’t. The king also had an inner circle referred to as “Friends” (Philoi), who acted as chief advisors. The problem with both terms is their use as common nouns as well as special titles. When is a friend a Friend?

Also, at least some of this was hereditary. Yes, making (or removing) Hetairoi was in the power of the king. But it was much easier to do the former than the latter, and even strong kings didn’t do the former early in their careers, never mind the latter. For many, becoming Hetairos was a rubber-stamp. They were Hetairoi because their fathers had been. We’re also not sure if the title was extended only to the eldest male in a household, or more than one could hold it at once, but for most, it was a birthright.

So, when Alexander took the throne, he was stuck with his father’s Somatophylakes (Bodyguard) and inner circle of advisors. He absolutely could not toss them out on their ear to install his own men. He had to proceed sloooowly. Which is why we don’t see Hephaistion as a Somatophylax even by the Philotas Affair, five years into ATG’s reign. He was clearly an advisor (Philos), but didn’t become Bodyguard until sometime later. Same thing with Ptolemy, who apparently got Demetrios’s slot—the Bodyguard (almost surely one of Philip’s) behind the actual conspiracy of Dimnos, not the made up one of Philotas. When he was executed, Alexander promoted Ptolemy to his slot. Note that Ptolemy was made Somatophylax before Hephaistion. Politics, family status, and probably age trumped personal affection.

If Hetairoi couldn’t be kings themselves (unless they were also Argeads), they were king makers, and kings had to take their influence into account. Especially new kings.

As a chieftain level society, Macedonia operated on “rule by clan” with the king being the senior male Argead. His brothers, sons, nephews, and male cousins might all have important roles, as did the women, although theirs were primarily religious and the running of the royal household. Yet royal women could do limited politicking in the way of donations (eurgetisms) to create goodwill, promote the family, or make alliances—as well as (of course) the alliance created by their marriage itself. Most of these roles were informal and ad hoc, rather than titular, if also expected of them. For instance, the king’s wives were just that: king’s wives. The title queen (basileia) wasn’t used until the Hellenistic courts of the Diadochi.

Ancient near eastern courts were more stratified, with more distinct roles. In fact, it seems that Macedon, from Alexander I onward, borrowed offices from the Achaemenid Persian court, including the Bodyguard and the Royal Pages (King’s Boys). So as early as the late Archaic Age, Macedonia looked east for how to formalize a court. Certainly Philip did it well before Alexander. The notion that Alexander’s Persianizing was somehow new is bull malarky.

Anyway, in the ANE, kings tended to fit one of two traditions: shepherd king or heroic king. The Sumerian kings and Hammurabi (Old Babylon) were both examples of the shepherd-king model. Heroic kings began with the Akkadian, Sargon the Great, then the neo-Assyrian kings, especially the Sargonids. Cyrus cast himself as a heroic king, but we see a shift back to shepherd kings with Darius the Great. Another aspect of ANE kingship were three chief expectations: win wars, build big shit, and administer justice.

Due to a much longer tradition of kingship extending from the Early Bronze Age, as you may imagine, these court systems developed much more in the way of formalized structures and offices. If these changed from king to king, at least by Bronze-Age Babylon (Hammurabi), then Neo-Assyria, access to the king was severely curtailed. At least the Persian kings got out and moved around on a sort of “King’s Progress,” but that was to check up on satraps. The average citizen saw them only at a distance. In contrast the Sargonids of neo-Assyria emerged from their palace complexes almost exclusively when going to war.

The Medes and Persians, like the Hittites before them, fit themselves into ANE traditions after they arrived in the area. Less is known about pre-ANE Hittites, but if they kept some unique religious traditions, when it came to How to Run an Empire, they used Akkadian and Egyptian precursors. Similarly, the Medes and Persians who came from the steppes, also adopted ANE patterns while retaining some traditions—again particularly religious (Zoroastrianism). We know a wee bit more about them prior; they (like Macedon) seem to have had chieftain-level monarchy with rule by clan, plus tribal princes, before conquering the whole area.

I hope that helps in understanding ancient eastern Mediterranean and near eastern notions of a court. We know less about the Odrysian Thracian and Illyrian kings to Macedonia’s north, but I suspect they were similar to early Macedon. Just tooling around Thrace, it was very clear to me that we’re looking at a shared regional culture between that area and Macedonia. Similar vibes attended my visit to Aiani (ancient Elimeia) and Dodonna (Epiros). I didn’t get up into Illyria, but what I do know of the archaeology suggests the same. ALL these cultures, despite the ethnic and linguistic differences, influenced each other. Yes, ancient Macedonia was at least “Greek-ish,” but we can’t and shouldn’t dismiss the impact on them from their northern neighbors.

Last, let’s consider the role of royal polygamy. Well back into the Bronze Age, ANE kings might marry several wives and also kept concubines for political purposes. That’s why we call it royal polygamy, not just polygamy. Royal polygamy might exist in a society that otherwise limits the number of wives anyone not the king can have.

Macedonian kings also practiced it, and Thracian and Illyrian, but on a more limited scale. Greeks and Romans, then Christians, depicted any polygamy as a “barbaric Oriental” (= morally corrupt) practice that supported their general view of Asia as soft and indulgent. (Sex itself wasn’t a vice, but too much sex was: uncontrolled desire.)

In later Europe, kings might have mistresses, but it wasn’t “official,” and they certainly didn’t have multiple wives. Christianity frowned on that. Even before, Roman emperors didn’t employ royal polygamy, although they did use serial monogamy—a long-standing practice back into the Roman Republic. Yet that required divorce. When the Christian church made marriage both a sacrament and a vow (not a contract, as it had been pretty much everywhere else), they made divorce impossible without either a wife’s death or religious shell games like annulment. Until Henry VIII, European kings were largely stuck with just one marriage.

Ancient courts didn’t have that problem. And from a political point of view, monogamy is a problem. It reduces the number of political ties available. Having royal polygamy offers more fluidity in possible heirs, and increases, sometimes exponentially, avenues for political alliance.

That said, the downside can be messy inheritance. Two of the more infamous inheritance disputes (other than Alexander’s) involved Esarhaddon, youngest son of Sennacherib, and Cyrus the Younger vs. Artaxerxes II. The latter dispute resulted in civil war (thank you, Xenophon, for telling us about it). As for Esarhaddon, he was so in danger from his older brothers, his mother kept him out of the capital until claimants were dead. There are others, but these two leapt to mind. There are also Egyptian examples, but I’m far less knowledgeable about those dynasties. And, as we see later in Europe, disputed successions can occur without polygamy!

Anyway, when it comes to selection of the heir, two things that matter in polygamous courts: status of the mother, and (for the ANE) whether she was queen. Not all wives were also queens. In the case of Esarhaddon, his mother Naqiʾa was of lower status and not a queen, so when his father named him heir, his older brothers (and their court allies) blew a gasket. Both Assyrians and later Achaemenid Persian kings could marry as many women as they wanted, plus take concubines…but the heir was expected to be from his Chief Wife, or Queen. Of “pure” blood. Cyrus the Younger’s argument against his older brother rested on a similar status technicality: he’d been born after his father became king, while Artaxerxes II was born before. We’d say Cyrus was “born to the purple.” But it was just an excuse; he was the ambitious one, and their mother favored him. If Macedonia didn’t have queens, the status of the mother mattered to being selected as heir there as well.

So these are some of the chief differences between ancient Mediterranean and near eastern courts, compared to later European.

#asks#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedon#ancient Persia#ancient Assyria#ancient Babylon#court societies#ancient court societies#Macedonian court#Philip II#kingship in the ancient near east#kingship in Macedon#Classics#tagamemnon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amazingly -and oh so not surprising-the way people conduct their selves and talk about Cleopatra's physical appearance still piss me off.

#cleopatra#yea she was greek Macedonian and nit nubian but you know what?#there was a movie abt egyptian Gods played by Gerlad Butler I think you dont have to be so picky about this smh#history#herstory#ancients#cricket chirps#I want tp watch her play mental chess with Ceasar and her court and hang out with her kids and waych her study 9 languages ect

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ive been reading the Persian Boy and I'm not suprised by the orientalism but I am disappointed

#Cipher talk#Tbc I don't mean the depiction of slavery#It's very specifically the depiction of Greek culture- I've gotten to the scene where Baogas has spears thrown at him by the 'squires'- as#Subtly 'better' than Persian culture#There's a scrap of deniability bc it's from Baogas's POV so he thinks the Greeks and Macedonians are completely weird and immodest#But what really gets me is how it portrays Alexander as outraged by the treatment of Greeks held in slavery and how it's all 'oh in Greece#They Never cut a boy' and there's no mention that Athenian 'democracy' had a large class of slaves as of yet#But even as we're told by the narrator how improper and immodest the Greeks and Macedonians are I can feel the author winking and nudging#Like 'oh look at how the Persian court is weighed down by ceremony its barely a real army they're decadent (in the way a conservative says#That about a culture) and look at how Baogas holds rivers as sacred and doesn't swim in them (you know the same water he gets sick from)#And the hypocrisy that he was groomed as a 'courtesan' as a literal child but is embarrassed by nudity'#Yeah Mary I can see the feelings of cultural superiority. I still remember that Athens was misogynistic as fuck and had plenty of issues

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Derveni Krater, a masterpiece of ancient metalwork. Found in Derveni, near Thessaloniki, in 1965. The funerary inscription on the krater writes it's dedicated to Astiouneios, son of Anaxagoras, from Larissa, an aristocrat. Some believe that this elaborate artefact was made in Athens while others suppose that it could be created in the Macedonian court, the date of its creation isn't clear as well, generally categorised as Hellenistic. What is most important though is the krater's vivid, playful and sensual decoration with satyrs, maenads and the pair of Dionysus and Ariadne. Usually, when someone died unmarried and the family had the means, such a depiction of a happy mated afterlife was preferred so to comfort the relatives for their loss. The relationship depicted between Dionysus and Ariadne seems more than sensual, the transparency of her clothing, along with his nakedness and their stances are more than revealing of their common passion.

Now at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece. The Derveni Krater may seem gold but it's actually made of bronze.

#mythology#art#symbolism#ancient greece#greek gods#ancient art#dionysus#ariadne#greek museums#antiquity#derveni krater#masterpiece#hieros gamos#satyrs#maenads#sensuality#ancient greek religion

435 notes

·

View notes

Text

.⋆◞❖°・.masterlists◡̈♡._

*:・゚✧.for you, 𝐼 ★•¸— ̶c̶o̶u̶l̶d̶ pretend like ❝.╭.+I w͟a͟s͟ h𝑎ppy°⊹when I was⋆◟̆๑𝓼𝓪𝓭; for you❝.:*。I could p͟r͟e͟t͟e͟n͟d͟˘.+*✦like I ɯαs▾₊˚𝓈𝓉𝓇𝑜𝓃𝑔 wh𝑒𝑛 I。*☆𝙝𝙪𝙧𝙩; ℐ wish・゚。❥love was ᴘᴇʀғᴇᴄᴛ❀⊰。as love ̶i̶t̶s͟e͟l͟f͟╮ⵓ❞¸I ɯısh all あ.♡my 𝔀𝓮𝓪𝓴𝓷𝓮𝓼𝓼𝓮𝓼 could ❞.ᔘ❀be 𝖍𝖎𝖉𝖉𝖊𝖓; I୭.° grew a 𝑓𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑟+*.♡:th𝑎t can't be ↬,。˚𝘽𝙇𝙊𝙊𝙈𝙀𝘿 in a↷.dream•that c͟a͟n͟'͟t͟ come ★*̣̥⁄⁄𝓽𝓻𝓾𝓮৴☽❰❪+

↳¸•.↑✿cited song: fake love by BTS.

➷°.[✩] BTS ╭⟡;💜

➷°.[✩] BLACKPINK╭⟡;🖤

➷°.[✩] ITZY ╭⟡;🧡

➷°.[✩] Stray Kids ╭⟡;💙

く く く EXO: Yandere Baekhyun (Romantic), Yandere Suho (Romantic). く く く TWICE: Imagine as Classmates.

➷°.[✩] Greek Mythology ╭⟡;⚡

➷°.[✩] Egyptian Mythology ╭⟡;𓂀

➷°.[✩] Historical Characters ╭⟡;📜

く く く The Lost Queen | Yandere!Alexander the Great ❝You woke up near a military camp without remembering how and why you got there, you didn't understand why they were dressed like ancient Greeks, all you knew was that you weren't safe and you needed to get out of that place as soon as possible. Too bad for you that you found yourself attracting unwanted attention from the Macedonian King and he won't let you go so easily.❞ The Lost Queen Series Masterlist

➷°.[✩] The Vampire Diaries // The Originals╭⟡;🧛

➷°.[✩] House of the Dragon╭⟡;🐉

➷°.[✩] Game of Thrones╭⟡;❄️

➷°.[✩] The Sandman╭⟡;⌛

➷°.[✩] Outlander╭⟡;🗿

➷°.[✩] Wednesday╭⟡;🎻

➷°.[✩] Brooklyn Nine-Nine╭⟡;👮♂️

➷°.[✩] Bridgerton╭⟡;🐝

➷°.[✩] Shadow and Bone╭⟡;☠️

➷°.[✩] Outer Banks╭⟡;💰

➷°.[✩] K-Dramas╭⟡;❤️

➷°.[✩] Reign╭⟡;👑

➷°.[✩] The Tudors╭⟡;🗡️

➷°.[✩] Hannibal╭⟡;🍽

く く く The Bloody Viscount | Yandere!Anthony Bridgerton ❝You had fallen in love with Viscount Bridgerton and he had fallen in love with you. The marriage seemed perfect, but then why did Anthony Bridgerton always come home late and bloodstained?❞ Prologue; Chapter 1; Chapter 2;

➷°.[✩] Percy Jackson╭⟡;🌊

➷°.[✩] Harry Potter╭⟡;🔮

➷°.[✩] A Court of Thorns and Roses╭⟡;🌹

➷°.[✩] A Song of Ice and Fire╭⟡🔥

➷°.[✩] Attack on Titan╭⟡⚔️

➷°.[✩] Naruto╭⟡🍥

➷°.[✩] One Piece╭⟡👒

➷°.[✩] Death Note╭⟡📓

➷°.[✩] Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug and Cat Noir╭⟡🐞

➷°.[✩] How To Train Your Dragon╭⟡🐲

➷°.[✩] Marvel╭⟡۞

➷°.[✩] Love Letters╭⟡💕

➷°.[✩] Love Letters II╭⟡💕

➷°.[✩] Kinktober 2023╭⟡🎃

#masterlists#masterlist#yandere au#yandere masterlist#yandere greek mythology#yandere historical characters#yandere bts#yandere percy jackson#yandere harry potter#yandere house of the dragon#yandere game of thrones#yandere a song of ice and fire#yandere blackpink#yandere the vampire diaries#yandere the originals#yandere love letters#yandere hotd#yandere anime

509 notes

·

View notes

Text

"During the reign of her husband the primary function of an Augusta was the orchestration of ceremonial at the imperial court, a highly stylised and intricate affair given the ceremonial nature of imperial life, which was based primarily around the Great Palace, a huge complex extending from the hippodrome to the sea walls, with its own gardens, sporting grounds, barracks, audience halls and private apartments; the Great Palace was the official residence of the emperor until 1204, though under Alexios Komnenos the imperial family usually occupied the Blachernai Palace in the north-west of the city, while there were other residential palaces in and outside of the capital. Empresses’ public life remained largely separate from that of their husbands, especially prior to the eleventh century, and involved a parallel court revolving around ceremonies involving the wives of court officials. For this reason an empress at court was considered to be essential: Michael II was encouraged to marry by his magnates because an emperor needed a wife and their wives an empress.

The patriarch Nicholas permitted the third marriage of Leo VI because of the need for an empress in the palace: ‘since there must be a Lady in the Palace to manage ceremonies affecting the wives of your nobles, there is condonation of the third marriage…’ While the empress primarily presided over her own ceremonial sphere, with her own duties and functions, she could be also present at court banquets, audiences and the reception of envoys, as well as taking part in processions and in services in St Sophia and elsewhere in the city; one of her main duties was the reception of the wives of foreign rulers and heads of state. Nor were empresses restricted to the capital: both Martina and Irene Doukaina accompanied their husbands on campaign.

The empress was also in charge of the gynaikonitis, the women’s quarters in the palace, where she had her own staff, primarily though not entirely composed of eunuchs, under the supervision of her own chamberlain; when empresses like Irene, Theodora wife of Theophilos, and Zoe Karbounopsina came to power they often relied on this staff of eunuchs as their chief ministers and even their generals. Theodora the Macedonian was unusual in not appointing a eunuch as her chief minister, perhaps because her age made such gender considerations unnecessary. The ladies of the court were the wives of patricians and other dignitaries: a few ladies, the zostai, were especially appointed and held rank in their own right. The zoste patrikia was at the head of these ladies (she was usually a relative of the empress),and dined with the imperial family."

Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium AD 527-1204, Lynda Garland

#history#women in history#women's history#byzantine empresses#byzantine empire#byzantine history#eastern roman empire#queens#historyedit#historyblr#medieval history#irene of athens

88 notes

·

View notes

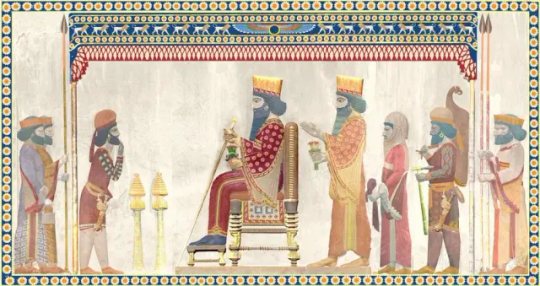

Photo

Perdiccas

Perdiccas (d. 321 BCE) was one of Alexander the Great's commanders, and after his death, custodian of the treasury, regent over Philip III and Alexander IV, and commander of the royal army. When Alexander the Great crossed the Hellespont and threw his spear onto the shore of Asia Minor, he and his loyal army began a ten-year journey that would take them to the far reaches of Asia, amassing an empire unlike any that had existed before it. However, the young king's sudden death in 323 BCE left a vast kingdom leaderless and in disarray; there was neither an immediate heir nor appointed successor. Perdiccas stepped to the forefront to offer a solution. With the king's signet ring in his hand, he attempted to keep the empire intact. Unfortunately, others loyal to the king maintained a different opinion. In the end, the various commanders took possession of their small piece of the territorial pie, leaving Perdiccas with only a slim chance of rebuilding what had already been lost.

Early Career

Perdiccas stepped to the forefront to offer a solution. With the king's signet ring in his hand, he attempted to keep the empire intact.

Much of what history knows about Perdiccas is not flattering, clouded by the hostile account in Ptolemy's history of Alexander and his conquest of Persia. Ptolemy I and Perdiccas had been constantly at odds with one another since Babylon, a conflict that would eventually lead to Perdiccas' death. However, other than Ptolemy's history, most dependable versions maintain that he was about the same age as Alexander (possibly a little older) and was the son of Orontes, a Macedonian noble from the House of Orestes, a royal family that had once ruled a small independent kingdom in the Macedonian highlands but whose power had been stripped by Philip II, Alexander's father.

Initially, Perdiccas was a page in the imperial court at Pella, but in 336 BCE he became a member of Philip II's elite infantry, a shield-bearer or hypaspist. Later in the same year, serving as a king's bodyguard, Perdiccas was one of many who pursued Pausanias, Philip's murderer. The reason for the murder: Pausanias believed the king had betrayed him and sought revenge. When the assassin's boot caught on a vine as he hopped onto his horse, he was immediately slain by his pursuers. History still debates whether or not Olympias, Alexander's mother, had anything to do with the death of his husband. Many still believe she encouraged Pausanias to kill Philip to ensure Alexander's ascension to the throne. One of these was Plutarch who wrote in his The Life of Alexander the Great,

… when he found he could get no reparation for his disgrace at Philip's hands, watched his opportunity and murdered him. The guilt of which fact was laid for the most part upon Olympias, who was said to have encouraged and exasperated the enraged youth to revenge… (11)

Continue reading...

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homosexuality in History: Kings and Their Lovers

Hadrian and Antinous Hadrian and Antinous are famous historical figures who epitomize one of the most well-known homosexual relationships in history. Hadrian, the Roman Emperor from 117 to 138 AD, developed a close friendship with Antinous, a young man from Egypt. This relationship was characterized by deep affection and is often viewed as romantic. There are indications of an erotic component, evident in Hadrian's inconsolable reaction to Antinous's tragic death. Hadrian erected monuments and temples in honor of Antinous, underscoring their special bond.

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion The ancient world was a time when homosexuality was not as taboo in many cultures as it is today. Alexander the Great and Hephaestion are a prominent example of this. Alexander, the Macedonian king from 336 to 323 BC, and Hephaestion were best friends and closest confidants. Their relationship was so close that rumors of a romantic or even erotic connection circulated. After Hephaestion's death, Alexander held a public funeral, indicating their deep emotional bond.

Edward II and Piers Gaveston During the Middle Ages, homosexuality was not as accepted in many cultures as it is today. The relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston was marked by rumors and hostilities, demonstrating that homosexuality was not always accepted in the past. Their relationship is believed to have been of a romantic nature, leading to political turmoil and controversies. Gaveston was even appointed Earl of Cornwall by Edward, highlighting their special connection.

Matthias Corvinus and Bálint Balassi In the Renaissance, there was a revival of Greco-Roman culture, leading to increased tolerance of homosexuality. Matthias Corvinus ruled at a time when homosexuality was no longer illegal in Hungary. The relationship between Matthias Corvinus and Bálint Balassi is another example of homosexuality being accepted during this period. Matthias Corvinus had a public relationship with Bálint Balassi, a poet and soldier. Their relationship may have been of a romantic nature, as Balassi was appointed as the court poet, and it had cultural influence.

These relationships between the mentioned kings and their lovers are remarkable examples of the long history of homosexuality in the world. In many cultures of antiquity and the Middle Ages, homosexuality was not as strongly stigmatized, demonstrating that homosexuality was not always rejected in the past.

Text supported by Bard and Chat-GPT 3.5 These images were generated with StableDiffusion v1.5. Faces and background overworked with composing and inpainting.

#gayart#digitalart#medievalart#queer#lgbt#history#gayhistory#KingsLovers#manlovesman#powerandpassion#gaylove

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in “Sal, what the fuck are you talking about?”: the middle Byzantine period.

The period from the mid-ninth century to the late 11th was defined by a resurgence in the empire’s fortunes, as the Abbasid Caliphate weakened and the bloody stalemate on the eastern border yielded to conquest, plunder, and expansion into regions that the empire hadn’t controlled for centuries. Domestic politics responded predictably to this influx of land, wealth, and prestige: the generals who led these conquests became immensely rich, respected, and in some cases powerful enough to make themselves emperor. Byzantium had never had a true hereditary aristocracy—when you died, your titles generally died with you—but these guys came pretty close, as a few dozen intermarried clans came to dominate both military and civilian politics for generations.

Making military leadership into a family business generally went well, as future commanders could begin learning the trade from a young age, instructed by the most experienced leaders in the empire. The downside was that their egos grew along with their conquests, and when they felt they weren’t being treated with the honor due to such a distinguished family, they had all the resources they needed to launch a rebellion against the throne. This happened again, and again, and again, and again; it’s no coincidence that this was the period when surnames became common among the wealthy.

In the palace, this era was defined by the so-called Macedonian Dynasty, a string of emperors and usurpers founded by Basil, a peasant from—you guessed it—the military district of Macedonia. Basil took the throne by becoming the emperor’s confidant and most trusted servant, before quite literally stabbing him in the back.

The next two centuries saw an alternating series of Basil’s descendants and usurpers take the throne, with coups and rebellions too numerous to list here. Basil’s heirs had a tendency to die while their sons were still minors (or to leave no sons at all), leaving a mad scramble for a new man to marry or kill his way into the imperial family. This was also the heyday of the court eunuch, as aristocrats looked for servants who would serve their family without trying to displace them in favor of their own sons; of course, plenty of eunuch did displace emperors in favor of their own friends and family, or else overshadowed them so completely as to become the functional ruler themselves.

Culturally, this period was quintessentially Byzantine. Emperors were very concerned with soft power, so they poured money into anything that would make them seem like the holy sovereign they considered themselves to be—histories, encyclopedias, churches, monasteries, public games, bejeweled reliquaries, and the like. Foreign ambassadors were feted with gold and silk in front of a throne that could rise from the floor until the emperor was looking down at the from the heavens. My favorite piece of writing from this era is the Book of Ceremonies, which spends hundreds of pages detailing the protocol for every imaginable public event, from the order of seating at imperial feasts to the proper weight of cargo loaded onto an army packhorse; it shows how the emperors tried to synthesize the importance of orderly, standardized, professional administration with the need to appear wise, just, and all-powerful to their subjects. It also shows how unbelievably wealthy the government was—very few states, at any point in history, had the time and resources and literal tons of gold to spend on court ceremonies that intricate and impressive!

I’ll spare you the list of emperors, their personalities, and the various schemes and subordinates that put them on the throne; that’s a whole separate post. Suffice to say that I think this is one of the most interesting eras of history, and I encourage everyone to learn more about it.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Arsinoë II] lived a dramatic and adventurous life, full of extreme highs and lows. In its course, she played a part in the courts of four kings, married three times (twice to a sibling or half sibling), saw two of her sons murdered, fled two kingdoms because her life was in danger, yet ended her days in great wealth and security and ultimately was deified. Born in Egypt (as the daughter of Ptolemy I Soter and Berenike), she departed as a teenage bride for marriage to Lysimachus, ruler of Thrace, parts of Asia Minor, and Macedonia. After her husband died in battle, she tried to protect the claims of her three sons to rule in Macedonia against the attempts of others to seize the kingdom. In support of this effort, she married one of these rivals (her half brother Ptolemy Ceraunus), only to have this marriage alliance end in a bloodbath that compelled her to return to Egypt, where her brother Ptolemy II had succeeded their father as king. Once back, Arsinoë married her brother (the first full brother-sister marriage of a dynasty that would make such marriages an institution). She died in Egypt, having spent her last years playing a prominent role in the kingdom. Throughout much of her life, Arsinoë controlled great wealth and exercised political influence, but domestic stability characterized only her last few years.

Bitter and sometimes violent struggles for the throne marked nearly her entire career [...] Her childhood experience coping with life in a court divided by succession politics colored virtually all the major decisions of her life. She played the roles of both victim and victimizer: Arsinoë likely had a hand in one murder but endured the slaughter of her younger sons. She possessed some political acumen and considerable drive, but boldness and the willingness to take risks were her most salient personality traits, the ones that led to her most dramatic successes and failures. Like most of the members of the Macedonian elite, male and female alike, Arsinoë single-mindedly and sometimes violently pursued kleos (fame, renown) for herself, her sons, and her dynasty.

— Elizabeth D. Carney, Arsinoë of Egypt and Macedon: A Royal Life

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wave of Pride

President Madison was not in attendance but, the First Lady represented him at the ball, which was also attended by the entire cabinet, most of Congress, and members of the Supreme Court. Hanging on the walls were the flags of Guerriere and the Alert, the latter captured by Captain David Porter and the Essex in the first engagement of the War. At around nine o’ clock rumors spread through the ballroom that Secretary Hamilton’s son would soon arrive with stunning news of conquest, and about ten o’ clock there was a commotion at the entrance of the hotel. Captain Stewart was called to the door, and he quickly beckoned Hull to join him. Hamilton then walked in through the curious and excited crowd, surrounded by his fellow naval officers. Unbuttoning his doublet to reveal his naval jacket, he was embraced by his parents and sisters and then strode towards Mrs. Madison, who sat in a place of honor in the center of the ballroom.

The crowd parted as Hamilton, carrying a bundle and accompanied by Hull and Stewart, approached the First Lady. Hull and Stewart pulled from the bundle the colors of the Macedonian, and others held it aloft above the heads of the three naval heroes. The crowd erupted in joy and the band played “Hail Columbia” as Midshipman Hamilton bowed and laid the Macedonian’s colors at Mrs. Madison’s feet.- “Ships of Oak Guns of Iron” Ronald D. Utt

…..when Macedonian’s flag was laid at the feet of Dolly Madison, Secretary Hamilton cried over the heads of the rapturous audience: “Never forget that it is to Captains Bainbridge and Stewart that you really owe these victories!” Unknown to the Secretary, unknown to any present in that hall, Captain Bainbridge at that very hour was far below the Equator, winning a reward he would infinitely have preferred. - “Preble’s Boys Commodore Preble and the Birth of American Sea Power” Fletcher Pratt

*artist comments under cut

“Lighting? Atmosphere? What atmosphere? I don’t even know what that is. Next thing you know, you’ll be telling me about color theory.

Excuse me as this piece of work is riddled with inaccuracies; didn’t bother to check myself until I started coloring and it was too late. So look, enjoy, and don’t talk/ correct me! 🤪

Congratulations on the fantasy promotion Archibald Hamilton, that uniform I accidentally gave you because I’ve been drawing it so much on unnamed naval officers looks good on you. If only you lived long enough to actually receive it.

#What burnout looks like#now I can focus on Thomas Macdonough#yay me i guess#war of 1812#1812 commodores#preble’s boys#age of sail#rosey art#naval history#us navy#isaac hull#Charles Stewart#You know what screw it#I’ve worked way too hard on this to wait til the 8th.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

where would i be able to read your monograph? especially about the ‘you are nothing without me’ incident

The Protracted Reality of Writing Academic Shit 😂

First, and assuming the asker means my Hephaistion-Krateros book, the quick answer is: It’s still in process, not even close to being in print. In the meantime, a number of my articles are available on academia-edu.

Now, to explain why the book is “still in process,” let me explain the monograph writing progression. IME, the average person uninvolved in academia is often surprised by the sheer complexity and time involved. (After all, why would you know if you don't need to?)

Below, I talk only about academic monographs, although I’ve also edited academic collections, and of course, have published a number of articles. I started to tackle fiction publishing too, but that quickly devolved into a long-ass post (even for me), so I’m sticking only to the topic the asker requested. It's long enough! Maybe I’ll do fiction later, assuming anybody wants to read that. (If so, put it in an ask.)

To write an academic book in the humanities typically takes years. There are several stages just to produce the initial manuscript, never mind getting it into print. I’ll outline the general process below, using my current project to illustrate the steps. One thing I’ve found consistently among both students and non-academics is utter surprise at just how extensive research/writing is. New grad students often think writing a thesis/dissertation is akin to writing a really long term paper. Oh, no. You will write it, submit it, get critique and feedback, go research some more and revise it, get critique and feedback, go and research yet more and revise it again … rinse and repeat. How long? Until it’s cooked. There’s not a set timeframe. It will always take longer than you expect. Always. I’ve been teaching grad students almost 25 years. I have yet to have any require less time than they first assumed.

Writing a monograph (including the thesis/dissertation, which is a type of monograph) is one of the toughest forms of academic writing. Papers/articles are much easier, and not just because they’re shorter, although that’s some of it. They also generally have a simpler point. They’re proving ONE thing, like a string.

A monograph presents a coherent, complex argument like a rope woven from several strings (the chapters). It’s not an edited collection by multiple authors in a single volume (or two), or even a collection of various essays by a single author. Collections may have a general topic, like, say, Macedonian Legacies (the collection we did for Gene Borza), or the one I’m editing now, Macedon and It’s Influences. Just trying to figure out a decent order for the varied papers can prove a challenge in these. If some of the papers actually do bear on each other … bonus! But the papers aren’t necessarily expected to come together at the end in any cogent way. A monograph’s concluding chapter should, however, bring together the chapters into a solid conclusion, like the arch’s capstone, holding it all together.

Yet the researcher may not know the answer to that until done with much of the research. After reading everything, and considering it, she may wind up in a different place from where she started. Like any good, responsible research, the researcher must be prepared to follow the data and facts, not cram them into a preconceived notion. I’ve changed some of my ideas and goals for my current monograph, as I no longer think I can do the project I originally intended because the nature of the sources get in the way too much. But I have a more interesting project as a result.

The first phase is research: pretty much for any academic field, period. How this progresses, and how quickly, varies with the individual, field, and topic. Furthermore, some of us are planners (that’s me), others are pantsers (e.g., they dive in and figure it out as they go: by the seat of the pants). But we all start with a question or observation, then go out to track down information about it. In history, sometimes we just read the primary sources/archival material and see what we find. Something strikes us, so we go on to read more, which produces either refined questions or entirely new ones.

Right now, I’m finishing up the initial stages of the research. Then I’ll start work on the chapters, which, yes, I’ve outlined as a result of my initial research. But those chapters may (and probably will) morph as I write them. It’s during the writing phase that the other, “attendant” research comes into play: chasing down all the references in other secondary sources for smaller points. Rabbit-hole time.

My initial research tends to be more measured. I read a while, stop to think—sometimes do stuff like write replies to asks on Tumblr while my brain churns. 😉 Then I go back and read some more. But the writing phase is where I can lose all track of time while running down just-one-more-citation-then-I’ll-stop. The last time I looked at a clock it was 3pm and now it’s 9pm, I’m weak with hunger, I really have to pee because I’m drinking too much tea, and the cats are mad because I’ve not fed them in hours. 😆 It’s two really different types of research for me.

Anyway, for the initial (pre-writing) stage, there are really two substages. The first is what I think of as archival work: e.g., getting down and dirty with the original (primary) sources, including digging into the Greek and Latin to see what it actually says, and if there’s something noteworthy in the phrasing. At this point, I may not really know what I’m looking for, except in the broadest sense. For my current project, I collected every single mention of Hephaistion and Krateros in the original sources. For all five ATG bios, I read them front to back, tagging all sorts of things, plus large chunks of important other books (e.g., the first part of book 18 of Diodoros, the extant fragments of Arrian’s After Alexander, plus a couple bios, esp. Plutarch’s Eumenes, etc.) in order to get a FLOW, not just collect things piecemeal. There are some passages that may not name Hephaistion or Krateros specifically, but they would include them. Piecemeal will always be incomplete, like trying to see a clear image in a broken mirror (a mistake I made with my dissertation, in fact, but I was young).

Then I assembled all that collected data on huge sheets, arranged by author for each man, so I can cross-reference and compare. I also did a deep-dive across 4 days, grabbing everything in Brill’s New Jacoby (BNJ), so I can also tag the original (lost) author cited in our surviving sources, where we know who it is. Not actually that many, but it’s useful and can prove significant. I want to see where the same information, or anecdote, crosses sources, and how it changes.

All of that (except adding the BNJ entry #s to my big sheets) is now done. The next step is figuring out what it all means. For that—and where I am right now—involves historiographic reading/rereading of secondary sources on the ancient authors. What is Curtius’s methodology? Arrian’s? Plutarch’s? What are the themes of each? What is the story they’re telling? They’re not just cut-and-pasters from the original (now lost) histories; they have agendas. What are they? How do Hephaistion and Krateros fit into those agendas? How do the sources use them? This is, to me, the really interesting piece.

It's also why this book will not be just a cleaned-up version of my dissertation, but a completely new look at Hephaistion, and now Krateros too. I haven’t even consulted my old dissertation chapters. I started over from scratch. Sure, I remember my main conclusions, and as I write, I’m sure I’ll go back to check things, but the same as I’d check anybody else’s.

I’d hoped to start writing by May, but I’m not quite there yet, in part because, between the Netflix series plus helping to write/edit a grant that I didn’t expect to have to do, I lost virtually all of February. Now, about half of April has been eaten by home repair/yard stuff plus small family crises. That’s just the nature of a sabbatical, especially if you don’t have a spousal unit or SO to take care of everything for you while you just write. 😒

Now I hope to start writing by mid/late May. But as this 9th International ATG Symposium is looming in early September, plus I go back to teaching in the fall, I’ll have to knock off by the end of July, if not sooner. Ergo, not a long writing time. I can do some more during winter break, but I probably won’t have a draft done until next summer. If I’m lucky. It is just not possible, at least for me, to write while teaching! As I do plan to present at least one (startling!) piece of my research as the ATG conference, I have a concrete deadline for a subchapter bit. Ha.

So, what happens after a draft is done? Well, if one is smart, one finds a reader or three. One just to read it for sense, but (if possible) another specialist to start poking holes in the arguments, noting secondary sources one forgot, and to offer general pushback in order to refine it all. This assumes your friends/colleagues actually have time to look at it, as they, also, are teaching and writing their own stuff. (I’ll go after my retired colleagues.) At the same time, one may also begin seeking an academic publisher.

It’s important to match the project to what the publisher is already publishing. It can also help, but isn’t necessary, to have an in: somebody known to/trusted by the editor of one’s broad field (ancient history, in my case) who can vouch for the scholarship. Submitting means writing up a summary of the work, perhaps including letters from colleagues/readers, etc., etc. I’m not even close to this stage yet, so I’m primarily going by the experiences of friends. At this point, it starts to dovetail a bit with fiction publishing. You’re on the hunt and do some of the same homework.

Once a publishing house requests the manuscript, they’ll farm it out to 2-3 readers to evaluate. This is the “refereed” part, as the readers will be specialists in the field. The publisher, who can’t be a specialist in everything, may ask for a list of names for these potential readers.

As with academic papers/book chapters, the book will come back from these readers with a vote on publishability, plus suggestions for improvement. The basic choices range from, “Go back to the drawing board; this has major issues and here they are” (e.g., not ready yet for publication). To, “It’s got good bones but here are improvements on chpts X and X, oh, and go read ___ works you forgot,” (e.g., revise and resubmit). To, “this is pretty solid as-is but could use a few more things” (e.g., revise but ready for a contract). You will NEVER get a “Publish it right now.” 🤣 It’s hard to say how much time this revising phase will take, as it depends entirely on the level of revisions requested. This is why it’s often wise to find a reader or three in advance, to make this phase less lengthy. Yes, books do sometimes get turned down entirely, with no “revise-and-resubmit,” but more often it’s one of the three above. And yes, sometimes an author may be unwilling to make the requested changes, so finds a different publisher, with different readers, hoping for a more positive outcome. Sometimes, with the revising stage, there’s a non-binding contract involved, but this seems to be usefully mostly for younger scholars who need some sort of proof for their RPT (Reappointment, Promotion and Tenure) committees.

Once a publisher gets a manuscript they believe is worthy, the author receives a (real) contract and is provided with in-house editors to fix grammar, sense, etc.: copy- and line-editing. What would (in fiction) be called “developmental editing” is what the refereed part entailed. This is the simple part. Getting TO the contract stage is the tough part.

The publishing house will then schedule the book with a publication date and discuss things like page-proofs, cover art, permissions, formatting, etc., including indexing, which most publishers either don’t do, or charge a high fee for. It’s almost always cheaper to hire an indexer separately. I’ve already got mine lined up for the Hephaistion-Krateros book. But that can’t be done until it’s typeset and through page-proofs as one needs, yeah, the page numbers. Ha. From contract to the book hitting shelves can take a full year, or more.

So, with the exception of those folks who are just writing machines, the average monograph is c. 5+ years, at least in the humanities. This assumes the luck to get a sabbatical, not trying to do it all crammed into summers or breaks.

So yes, I’m still a couple years from this book seeing print. And that assumes there’s not a lengthy revise-and-resubmit process because my readers don’t like my conclusions.

#asks#Hephaistion#Krateros#monograph on Hephaistion and Krateros#Hephaestion#Alexander the Great#writing an academic monograph#academic publishing#Macedonian Court

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Alexander Romance, a medieval collection of mythical stories starring Alexander the Great, Alexander's father isn't Philip II of Macedon. It's Nectanebo, the last Egyptian pharaoh (after Alexander conquered Egypt, pharaohs were Greek). In the Romance, Nectanebo was a magician and trickster who supposedly fled to Macedon after a military defeat and found a place in the Macedonian court as a fortune-teller. He told the queen that she would be impregnated by a god. He then disguised himself as that god and slept with Olympias, fathering Alexander.

Here’s a French depiction of that moment from the 1400s:

You can read the whole piece here:

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antony after Caesar

The first coin with Antony's portrait, struck within two months of Caesar's assassination. Antony is shown veiled and bearded as a sign of mourning.

Antony’s career independent of Caesar started with the Ides of March 44 BC. The murder of Caesar sent shock waves through the population, giving rise to diplomatic activities with the purpose of both conciliation and the factionalism, resulting power struggles and eventually civil war. As Caesar’s seeming successor, Antony had to strengthen his own position without provoking immediate conflict. Would he be able to lead the Republic? He held imperium of all the armed forces, which was the most important factor, not only to rise to power, but also to keep it as Sulla, Pompey and Caesar before him. Huzar notes “the fact that Caesar made Senate and Comitia truly ineffectual lies behind the helplessness of these bodies”.

After Caesar’s death Antony brilliantly took control (Cass. Dio 43.27.1; Cic. Ad. Fam. 4.6.3; 6.16; 15.3-4), while also ensuring his safety as he was guarded by his praetorian guards and 6000 veterans. In order to get the mob on his side he swayed them with his passionate speech at Caesar’s funeral by his oratorical talent and his exhibitionism. Even though Suetonius (Jul. 85) says he held no formal speech, Cicero and Plutarch (Ant. 4.3 9-4), among others, describe how he swayed the people to rage, inciting them to burn the body and buildings and assault the murderers. With the acquisition of Caesar’s papers and money Antony was in a strong position. Although Cicero accuses Antony of falsification “on a colossal scale” (Phil. 2.36), and forgery of the papers may have been possible on a practical level, it could not be proven, then or now.

Antony, however, was not deterred by the common belief that he was resorting to forgery; and a little later he obtained a sum of money from the Cretans in return for granting them, again on the authority of Caesar, future exemption from taxation. His justification is that he needed funds for the upholding of his authority, and for winning the support, for instance, of Caesar's veterans; and it is certain that, he spent the bulk of the money in the public interest.

Antony continued to use the popular assembly to ensure Rome and the empire does not fell into anarchy. Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul for six years, and the retention of four Macedonian legions, which he transferred to Gaul. Since his campaign in Gaul (off and on between 54 and 51 BC), Antony must have realized the importance of being in control of especially Cisalpine Gaul, the “gateway to Italy".

Legislation like municipal legislation on qualifications for holding office and census regulations continued Caesar's plans. Unfortunately, we hear of his programs chiefly from his enemies. When a judiciary law extended eligibility for jury duty to men of centurion and even legionary rank and transferred the hearing of final appeals from the courts to the people, Cicero charged that Antony was packing the courts and fostering mob violence. The democratic measures were never given a fair trial, for with Antony's other measures, they were cancelled in 43 B.C. When Antony failed to hold the scheduled election of the censors owing to the unwillingness of the majority of the senate, but did issue an edict on sumptuary laws, it became the object of ridicule because of his reputation. Nevertheless, that Rome remained calm during these days of transition indicates a strength and stability in Antony's administration of the state.

#mark antony#marcus antonius#julius caesar#rome#roman history#ancient rome#roman republic#roman empire

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Macedonian Restoration period of the Eastern Roman Empire (958-985) would make for a really cool Game of Thrones style TV show.

It's got lots of battles, court intrigue, blood feuds, and murder.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

.navigation

��.。Welcome to my blog! My name is Larissa, but feel free to call me Lari or Lady L, which is how you know me. I'm Brazilian 🇧🇷 and I was born on October 15th. English is not my first language. My pronouns are she/her and I am bisexual 💖💜💙. I am Libra ♎️ and INTP.

⤷♡. If you want to support my work or to just tip me, can you buy me a coffee? ☕️

⤷✿.Here I've gathered all my series, masterlists and some additional things to make them easier to find. Enjoy my blog, dear reader.

© aphroditelovesu, 2022. all rights reserved. do not translate or repost my work without my permission. you are free to use my edits, but I only ask that you credit me.

⤷♡.+ disclaimer: some of my works may have nsfw content in addition to the yandere genre. if you are sensitive to these topics, I recommend not reading.

⤷♡.+ genre: yandere/dark!au.

⤷♡.+ Requests are OPEN. Asks and concepts are open.

⤷♡.+ character ai: aphroditelovesu.

⤷♡.+ Rules and Fandoms List;

⤷♡.+ Emoji Prompt List + Prompts List;

⤷♡.+ Wips; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; 7; 8;

⤷♡.+ Commissions;

‘‘Love you so bad, love you so bad, mold a pretty lie for you.’‘ ˚˖੭ Fake Love, BTS.

⤷♡.+ BTS; 💜

⤷♡.+ BLACKPINK; 🖤

⤷♡.+ ITZY; 🧡

⤷♡.+ Stray Kids; 💙

➷ EXO: Yandere Baekhyun (Romantic), Yandere Suho (Romantic).

➷ TWICE: Imagine as Classmates.

⤷♡.+ Greek Mythology; ⚡

⤷♡.+ Egyptian Mythology; 𓂀

⤷♡.+ Historical Characters; 📜

➷ The Lost Queen | Yandere!Alexander the Great ❝You woke up near a military camp without remembering how and why you got there, you didn't understand why they were dressed like ancient Greeks, all you knew was that you weren't safe and you needed to get out of that place as soon as possible. Too bad for you that you found yourself attracting unwanted attention from the Macedonian King and he won't let you go so easily.❞ The Lost Queen Series Masterlist

⤷♡.+ The Vampire Diaries + The Originals; 🧛

⤷♡.+ House of the Dragon; 🐉

⤷♡.+ Game of Thrones; ❄️

⤷♡.+ The Sandman; ⌛

⤷♡.+ Outlander; 🗿

⤷♡.+ Wednesday; 🎻

⤷♡.+ Brooklyn Nine-Nine; 👮♂️

⤷♡.+ Bridgerton; 🐝

⤷♡.+ Shadow and Bone; ☠️

⤷♡.+ Outer Banks; 💰

⤷♡.+ K-Dramas; ❤️

⤷♡.+ Reign; 👑

⤷♡.+ The Tudors; 🗡️

⤷♡.+ Hannibal; 🍽

➷ The Bloody Viscount | Yandere!Anthony Bridgerton ❝You had fallen in love with Viscount Bridgerton and he had fallen in love with you. The marriage seemed perfect, but then why did Anthony Bridgerton always come home late and bloodstained?❞ Prologue; Chapter 1; Chapter 2; ➷ The Shadow of the Golden Dragon | Yandere!ASOIAF/HOTD/GOT ❝You have always been an avid reader and your greatest passion was delving into the pages of "A Song of Ice and Fire" by George R.R. Martin. You knew every character, every twist and every detail of the Seven Kingdoms as if they were part of your own life. But what you never imagined is that an unexpected encounter with a mysterious antique book seller would change your life forever.❞ The Shadow of the Golden Dragon Masterlist

⤷♡.+ Percy Jackson; 🌊

⤷♡.+ Harry Potter; 🔮

⤷♡.+ A Court of Thorns and Roses; 🌹

⤷♡.+ A Song of Ice and Fire; 🔥

‘‘We were born to be alone but why we still looking for love?’‘ ˚˖੭ Lovesick Girls, BLACKPINK.

⤷♡.+ Attack on Titan; ⚔️

⤷♡.+ Naruto; 🍥

⤷♡.+ Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug and Cat Noir; 🐞

⤷♡.+ One Piece; 👒

⤷♡.+ How To Train Your Dragon; 🐲

⤷♡.+ Death Note; 📓

‘‘Don’t you know that you’re toxic?’’ ˚˖੭ Toxic, Britney Spears.

⤷♡.+ Marvel; ۞

‘‘I wish you would love me again, no, I don't want nobody else.’’ ˚˖੭ Love Me Again, V.

⤷♡.+ Love Letters; 💕

⤷♡.+ Love Letters II; 💕

⤷♡.+ Kinktober 2023; 🎃

➷ A Black Rose | Yandere!Ian Daerier ❝A cruel and narcissistic reaper falls in love with the woman he was supposed to take the life of.❞ Oneshot;

#navigation#masterpost#masterlist#masterlists#rules#fandoms list#prompts#emoji prompt#prompt list#yandere au#love letters#wips#yandere#dark au#📌 pinned post

365 notes

·

View notes